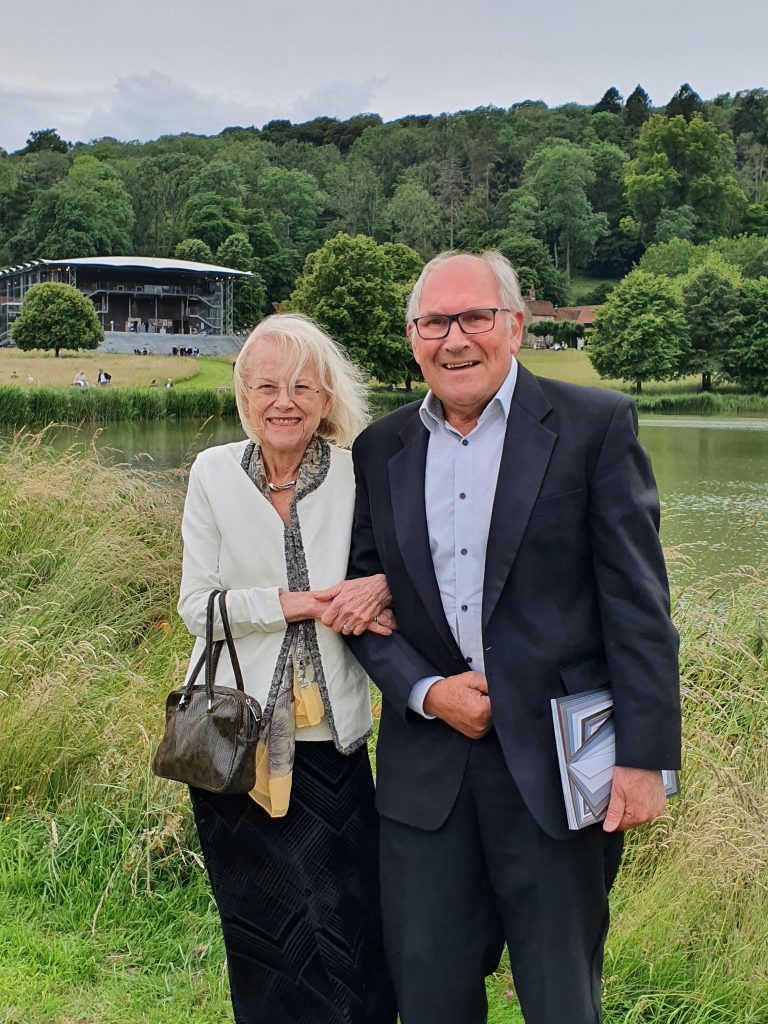

So following our trip to Glyndebourne, we’ve twice been to the other famous country house opera venue Garsington Opera at Wormsley, the estate of Mark Getty in Buckinghamshire. The operas take place in a fabulous glass pavilion where natural light and open access are often used to good effect by the production teams. There was ample time to take a glass of refreshing bubbles and go for a stroll round the lake in the deer park before returning to the opera house for the main events.

An afternoon stroll

The Opera Pavilion

And now for the reviews:

HIGH JINKS – LOW NOTES

Der Rosenkavalier 24 June 2021

So just ten days after Kat’a Kabanova at Glyndebourne it’s off up the M40 to the Wormsley Estate at Stokenchurch to see Garsington Opera’s new production of Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier. Before we get to the music there’s that awful poser: if you could only ever do one country house opera trip, would it be Glyndebourne or Garsington? (Other country house operas do exist, but…) Hideous rhetorical question: they are both wonderful experiences in superb locations in beautiful English countryside. They both attract world class singers, directors and orchestras, stage both classic pieces and new work – recently The Skating Rink at Garsington and Hamlet at Glyndebourne – and have excellent auditoria for listening to music in very contrasting styles. The honeyed wood of Glyndebourne envelops you in a different way from the glass box at Garsington where the outside often comes into the opera. I’m fortunate – I don’t have to make this difficult choice.

And so to the opera, a maiden production at Garsington. Der Rosenkavalier is Strauss’s bit of Viennese fluff – self-described in the libretto as a farce. There’s nothing wrong with farce but if you do it, do it well. And director Bruno Ravella does it very well indeed. The set is full of massive plaster curlicues slanting back from a broad light box style proscenium frame which changes colour with the mood of the scenes. We open to find a rosy-cheeked. Rose-bearing cupid emerging from below the stage to observe the lovemaking of the Marschallin and Octavian. He returns throughout the piece perhaps reminding us that love can pop up in the most unusual places and cause grief as well as the ecstasy which the principals are enjoying at the start in a massive four-poster bed. Miah Persson is an imposing Marschallin with her clear diction, gorgeous voice and stage presence. Hanna Hipp’s Octavian is all youthful enthusiasm and first flush of love with her cropped hair giving her credibility to the trouser role. The romantic subtlety of the score that accompanies and drives their exchanges is well modulated by Canadian conductor Jordan de Souza making his Garsington debut in charge of the Philharmonia. Whereas the reduced forces resulting from Covid social distancing helped me hear Janacek’s score more clearly, here some of the lushness of the score was missing occasionally but this was only marginal and the disparate elements were combined into a satisfying accompaniment to the action.

The production team carry this excellent work into the change of mood when Derrick Ballard’s Ochs enters the scene to ask for help in his marriage pursuits and then lecherously chases the Octavian-turned-Mariandel character in rambunctious farce. Ballard’s mastery of the lowest notes in the score is impressive and he does lowlife wannabe aristo very well. I think the production slightly loses the class distinctions that Strauss spiked so well in the libretto. The first act conclusion with the Marschallin telling Octavian their love will not last is a wonderful exchange between the two sung with real emotion – a tender and moving passage after the high jinks with Ochs.

In Act 2 we meet the venal Fanimal household with their marriage-fodder daughter Sophie the only character to emerge with any grace. Madison Leonard sings Sophie with a fine range of emotion from horror at the thought of being wed to Ochs to the tender realisation of her feelings for Octavian. The orchestra embrace the contrasting colours of the score with enthusiasm. The corny waltz, ominous social storms and lyrical arias demonstrate Strauss’s mastery of orchestration to evoke every mood.

Returning for Act 3, I was thrown off kilter by the addition of a second slanted proscenium frame which in a powerful way suggested the upheaval in Viennese turn of the century society that is otherwise perhaps a little underplayed in the production as a whole. More rambunctious behaviour with music to match leads us to the breathtaking trio between Persson, Hipp and Leonard sung with moving sensitivity and then the Octavian/Sophie finale sent us out of the Garsington glass palace sated by music and drama touching every nerve from laugh-out-loud to tearful empathy and the sense of witnessing a period of societal upheaval and personal maturation.

A TOE IN THE WATER

Eugene Onegin 5 July 2021

Let me start by saying that I take my tea and coffee strong, black and without sugar and I quite like my music that way too. So I’m not a huge fan of Tchaikovsky who seems to like his with milk and sugar, some sweeteners and then maybe some honey stirred in for good measure. But this is his most famous opera, my friend had seen it several times but I was an Onegin virgin so we ventured to Wormsley to give it a go. Dip a toe in the water and see how it feels.

What a delight! Singers 10 out of 10; Orchestra 9; Production 10; Story 5 but then it is opera and we can blame Pushkin; Music 7 – better than I feared but not something I’ll be rushing to catch again. So why the other scores?

That first big chorus when the workers come (literally) in from the fields, once again, as a while back in Fidelio, using the glory of the Garsington glass box to bring the outside in. What joy to hear such strong voices in such a Russian-sounding, bass heavy number. The poise and delivery of the demure Tatyana from debutante Natalia Tanasii were perfect, maturing from her girly longing for Onegin to her final Act stern resolve in rejecting him as he had spurned her – no hellish fury visible here but an icy dismissal all the while holding back her tears. Her skittish, flirtatious companion Olga was ably presented by another Garsington debutante Fleur Barron. It’s remarkable how much better as actors singers have to be these days than when I first went to opera back in the 1960s. I thought Sam Furness was a little underpowered as Lensky to start with but grew into his role as the evening progressed. As Onegin, Jonathan MacGovern sung his scheming, despicable part with total conviction and fine voice – he deserved boos at the curtain call as the villain of the piece. All others contributed to near faultless performances – an arch French aria from Colin Judson’s Triquet and Matthew Rose’s Gremin a stolid if dull husband for Tatyana but totally convincing in the sincerity of his love for her.

The Philharmonia under conductor Douglas Boyd obviously relished the score – all still a bit too programmatic for my taste but masterfully delivered, just once or twice overwhelming the vocalists. Huge energy and enthusiasm emanated from the pit with slightly larger forces than for the Rosenkavalier we saw a few weeks ago.

The production in the hands of director Michael (no relation) Boyd, designer Tom Piper, lighting designer Malcolm Rippeth and choreographer Liz Ranken did justice to every aspect of the story. The first Act log cabin elements moved around by the aforementioned peasants worked well to suggest a peasant izba regarded by Onegin with disdain whose no doubt more luxurious dacha was just a few miles but a lot of rungs on the social ladder away. His arrival preceded by a brilliant coach of whirling umbrellas pulled by prancing Cossacks was masterful and later upstaged by the arrival in similar vein of a full coach-and-four. So with the glove thrown down and the challenge accepted, we set off for our picnic in a tent overlooking the cricket ground.

We managed to sprint through the drizzle without becoming too wet, but as we dined on our very tasty and varied picnic provided by Feasts at Garsington, the heavens opened and a kind neighbouring diner lent me her umbrella to run to the car and fetch my large one to cover us both on the way back through the deluge. Toe in the water became foot in the pond but the long interval and discussion of the show are always an important part of the charm of country house opera and a little inclement English weather won’t detract from that.

The Garsington carpenters deserved double pay as the struts that normally support the flats were heavily featured in many scenes, most notably in the duel scene with liberal use of dry ice and low angle lighting suggesting a cold and misty morning. But did we really need those premonitory bangs in the score Peter Ilyich? – less is more a lot of the time.

When the log cabin sets give way to the huge mirrors for the final Acts, I was reminded of Michael Frayn’s Audience from 1991 and could barely stop myself waving to our reflections from the auditorium as we were encouraged to do on that occasion. The choreography of the ball scenes with waltz, mazurka and polonaise all beautifully delivered was exquisite and funny. In the big confrontation on Onegin’s return the dancers’ protective circle around Tatyana was most affecting, keeping her from Onegin’s gaze and clutches now the little country mouse had become an object of both social and sexual desire.

In short, despite my misgivings, another brilliant evening at the opera with a dear friend, an excellent production in every aspect using skilfully the effects that Garsington’s opera pavilion permits.